The Railway Pattern

When talking about the Railway Pattern, the analogy uses train railroad tracks. Until now, we’ve only looked at straight pipelines where data passes through and is transformed at each step. In essence our train tracks were straight, single line tracks. The Railway Pattern gives us a way to introduce branching logic to a pipeline. It gives us a track switch that can change the flow and cause the train to leave one track and switch to another.

The Railway Pattern introduces branching logic to a pipeline.

Contents

Pipeline is the “Happy Path”

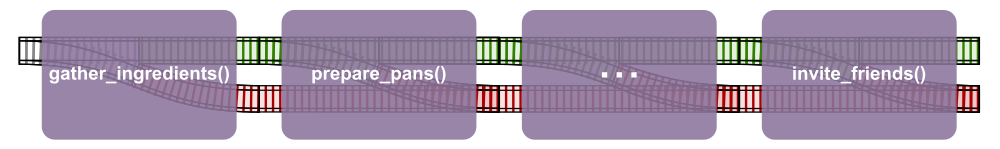

Pipelines read well going from top to bottom. Each step in the pipeline performs some operation. The step’s return value is piped into the next step. Let’s look at a pseudo-code pipeline used to bake a cake.

defmodule Life.Cooking do

def bake_cake(%Person{} = person, %Recipe{} = recipe) do

%{person: person, recipe: recipe}

|> gather_ingredients()

|> prepare_pans()

|> mix_dry_ingredients()

|> mix_wet_ingredients()

|> mix_wet_and_dry()

|> pour_batter_to_pans()

|> bake(recipe)

|> allow_cooling()

|> frost_cake()

|> invite_friends()

end

endI start the pipeline with a map holding the data of a person and the recipe being used. Each step in the pipeline gets me closer to creating my confection and inviting friends to indulge with me.

This pipeline reads as the “Happy Path”. If everything goes well, then I’ll have a delicious cake ready to share with my friends. But what if it doesn’t go well? There are lots of things that could go wrong. Here are some possible issues that could occur in the steps.

- I don’t have all the ingredients

- I don’t have a cake pan

- I spill all the wet ingredients while mixing

- My oven is broken

- I burn the cake

If any of these steps go really wrong, I do not want to invite my friends over to eat a cake that doesn’t exist!

I need a way to run through the steps of the pipeline and handle if things go well or if things go wrong.

The Railway Pattern helps me do this!

Forking the Flow

Let’s start with the first step in the pipeline. If I have all the ingredients, I want to proceed with my cake project. The code for the first function might look something like this…

defmodule Life.Cooking do

# ...

def gather_ingredients(%{recipe: %Recipe{ingredients: ingredients}} = data) do

case Ingredients.find(ingredients) do

{:ok, found_ingredients} ->

# Found all the ingredients needed!

# Add the found ingredients to the map

{:ok, Map.put(data, :ingredients, found_ingredients)}

{:error, reason} ->

# One or more required ingredients are missing

{:error, "Cake ingredients missing: #{inspect(reason)}"}

end

end

endMy function has two possible return values. An {:ok, ...} tuple with updated data being passed on and an {:error, ...} tuple explaining why it failed.

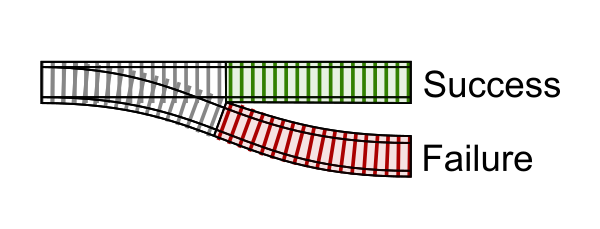

Essentially, what I’ve just done is created a function with one entry point but 2 possible exit paths. I forked the flow that the code can take and created a second “failure” track.

The Next Segment

The second step in the pipeline is prepare_pans/1. This second step, or second segment of track, must deal with there being two possible tracks coming in.

This function might look something like this…

defmodule Life.Cooking do

# ...

def prepare_pans({:ok, %{recipe: %Recipe{equipment: equipment}} = data}) do

case Equipment.find(equipment) do

{:ok, found_pans} ->

# Found all the right kinds of pans needed!

# Add the equipment to what we have available

{:ok, Map.put(data, :equipment, found_equipment)}

{:error, reason} ->

# Unable to find all the needed equipment for the receipe

{:error, "Equipment missing: #{inspect(reason)}"}

end

end

def prepare_pans(error), do: error

end

There are 2 function clauses here. The first pattern matches on it being an {:ok, data} tuple. The second clause takes whatever else it was (because it wasn’t OK with what was expected) and treats that as an :error by just passing it along. This “bypass” function is the “failure” track. It does nothing but provide a way through this function when it didn’t succeed. Our function looks like this.

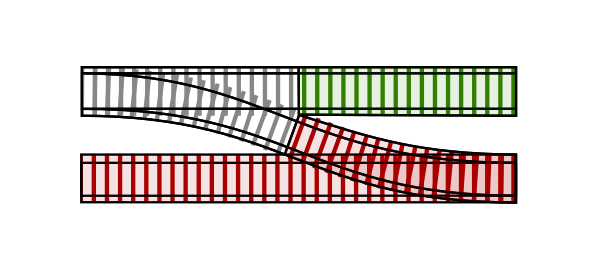

Putting our first two functions together, our track looks like this…

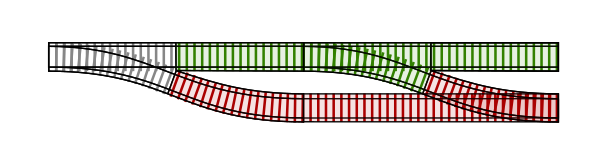

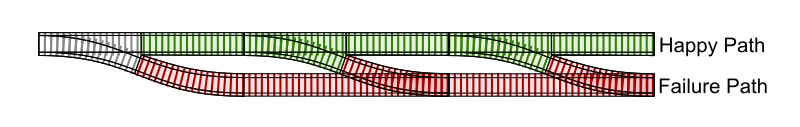

If we were to continue building out steps in our pipeline, we would see that each step provides a success track and a failure track. A full string of successes creates our “Happy Path” all the way to the end. However, at any point in the flow, something can go wrong and shunt the flow onto the error path.

Notice that once on the error path, there is no way back onto the success path. The track switches only go the one way. It either all goes perfectly or something fails and we end up on the failure path and stay there through the end of the pipeline.

No Embarrassment Guarantee

My initial concern was wanting to avoid the embarrassment of inviting friends for cake if the baking project fails. To guarantee this, my invite_friends/1 function only needs to send out the invitations when a recognized pattern for success is seen. In this case, when a {:ok, data} tuple is received. Any problem encountered along the way directs the Code Flow to the failure path. With an invite_friends/1 function clause that handles the {:error, reason} then I am guaranteed a no embarrassment evening. At least as far as the cake is concerned.

The same can be said for your application. You don’t want to send out an email thanking your customer or user for an action that failed somewhere along the way!

The Railway Pattern gives us an elegant way to express the “Happy Path” that clearly shows the workflow. It adds branching logic to our pipelines to take the flow off the Happy Path when something goes wrong.

Strengths and Weaknesses

As with everything, there are strengths and weaknesses. Let’s consider some with the Railway Pattern.

Strengths

The pipeline literally outlines our “Happy Path”. As developers, we typically code the Happy Path first anyway. As an afterthought we return to think about potential problems. This pattern communicates the “big picture” of what is going on without being muddied with the details of how it happens yet. Take another look at the pipeline:

%{person: person, recipe: recipe}

|> gather_ingredients()

|> prepare_pans()

|> mix_dry_ingredients()

|> mix_wet_ingredients()

|> mix_wet_and_dry()

|> pour_batter_to_pans()

|> bake(recipe)

|> allow_cooling()

|> frost_cake()

|> invite_friends()This code is highly readable. The big picture is laid out and the developer’s intent is clear. Additionally, this pattern lends itself well to refactoring and even re-arranging steps if needed.

Weaknesses

The drawbacks for the Railway Pattern are:

- You must create at least 2 functions clauses for each step in the pipeline. One to act as the bypass failure function clause and one or more to handle the success path.

- Doesn’t adapt well to functions defined in other modules that weren’t created with your pipeline in mind. Therefore all the functions in your pipeline must be created for the purpose of the pipeline. The functions can delegate out to other modules and functions, but they need to be created for the pipeline.

When to use the Railway Pattern?

When the benefits and drawbacks are all considered together, it’s fair to ask, “When should I use the Railway Pattern”?

As a starting point and a rule of thumb, it makes sense for a workflow that can all be defined in a single module. An example could be a module like AccountRegistration. The entire module is dedicated to a single task. This works well for a workflow with multiple steps but there are really only two possible outcomes. It all worked or it didn’t.

Each step in the pipeline can be a public function with it’s own set of unit tests. The top-level entry point function defines the pipeline in a clear, declarative way. The rest of the module is concerned with how to perform the steps.

The Railway Pattern is a coding pattern much like Object Oriented patterns you may already be familiar with. There are many different and appropriate ways to use it. It is a tool that is now available to you. Be willing to try it out in a project and develop a feel for where it works best for you. If it isn’t the right fit, you can refactor the code into a different pattern.

What Should I Pipe?

You don’t have to keep piping a map of data through to each function, it can literally be anything from one step to another. The next function in line just needs to accept the success and failure outputs from the previous function.

Does it have to be an :ok or :error tuple? No! However, using an :ok and :error tuple work well because they make it easy to pattern match and tell the difference between being on the “success” track or the “failure” track. Whatever lets you correctly and reliably tell the difference works.

Practice Exercise – Award Points

The following exercise uses the downloaded project. Remember you learn best by doing! Use the tests to verify you have a working solution.

Make sure to check out the solutions after you have the tests passing. It can be helpful to see other ways to express the solution.

Specification

Given a User struct and a number of points to award, create a pipeline using the Railway Pattern that does the following things:

- validates that the user is active

- validates that the user is at least 16 years old

- checks that the user’s name is not on the blacklist of

["Tom", "Tim", "Tammy"] - increment the user’s points by the desired number

Only increment the user’s points if all the previous steps are valid and pass. If any of the checks fail, return an {:error, reason} where reason is the explanation of why it failed.

Two ways to Test

The tests to focus on are in test/code_flow/railway_test.exs. There are two major sections of the test file.

- A

describeblock that tests the full pipeline - A separate set of tests for each step in the pipeline

The describe block award_points/2 tests the 4 conditions in the above specification. How you name each function in the pipeline is up to you. The function names are “internal details”. However, if you want more guidance or suggestions, the set of tests for each step can help walk you through it in smaller chunks.

If you don’t want the step-by-step tests, then either delete them or comment them out.

To run all the tests inside the award_points/2 describe block:

mix test test/railway_test.exs --only describe:"award_points/2"To run the tests that cover each specification step, you can run them individually:

mix test test/railway_test.exs:30

mix test test/railway_test.exs:35

mix test test/railway_test.exs:40

mix test test/railway_test.exs:45Tips

Here are a few tips to help you get started:

- One way to start a pipeline using TDD is to start by creating your pipeline steps.

- Tests won’t run if the code doesn’t compile. Either comment out the steps you aren’t ready to work on OR create function stubs so it compiles.

- For checking the name against the blacklist, you can use an

inguard clause or inside the function you can useEnum.member?/2to check against the list.

Recap

The Railway Pattern uses pipelines, pattern matching, and multiple function clauses to create an elegant control flow solution. Here are a few points to keep in mind about the Railway Pattern:

- Since the Railway Pattern needs to pipe data through each step, it works best when there is a structure that can be piped through.

- The top-level pipeline is a clear declaration of what is happening and defines the “happy path”.

- When the flow leaves the “happy path”, it goes onto the “failure path” and flows through the rest of the pipeline on that track.

- It works best when you control the functions that implement each step. This usually means the functions are created for the workflow and live in a module together.

11 Comments

Comments are closed on this static version of the site.

Comments are closed

This is a static version of the site. Comments are not available.