The “with” Statement

Pattern matching is everywhere in Elixir. This holds true for the with statement as well. To understand how it helps, let’s start by looking at a problem it helps fix.

Contents

Solving a Problem

Let’s look at an example of the case statement where we want to process some data in multiple steps.

This is a simple example just so we can focus on the steps involved and still have something easy to copy and paste into IEx so you can play with it.

We start with a simple map. The following steps happen in order:

- Fetch the

:widthvalue from the map - Fetch the

:heightvalue from the map - If we got both values, multiply the values and return the result

data = %{width: 10, height: 5}

case Map.fetch(data, :width) do

{:ok, width} ->

case Map.fetch(data, :height) do

{:ok, height} ->

{:ok, width * height}

error ->

error

end

error ->

error

endThis created an awkward nested case statement. It isn’t very readable or pleasant. Seeing the “success path” requires more mental parsing. Nested case statements are a code smell. When you see nested case statements in your code, you may want to use a with instead.

Introducing with

The with statement is a very common pattern. The with statement documentation says it is:

Used to combine matching clauses.

https://hexdocs.pm/elixir/master/Kernel.SpecialForms.html?#with/1

Let’s re-write this using a with statement to see how it works.

data = %{width: 10, height: 5}

with {:ok, width} <- Map.fetch(data, :width),

{:ok, height} <- Map.fetch(data, :height) do

{:ok, width * height}

end

#=> {:ok, 50}

This is functionally equivalent to the nested case example!

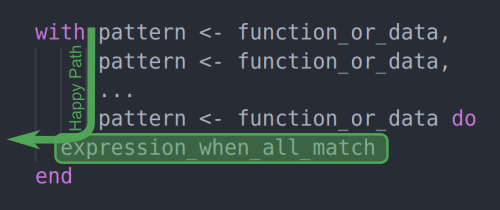

This with supports a series of clauses. When all clauses match, the do block is evaluated and is returned as the result. A with clause is made up of a pattern on the left, a left-pointing arrow <-, and data on the right.

The series of clauses is evaluated top down with the “success result” returned from the do block. This is our “happy path”!

What happens when one of the clauses fails?

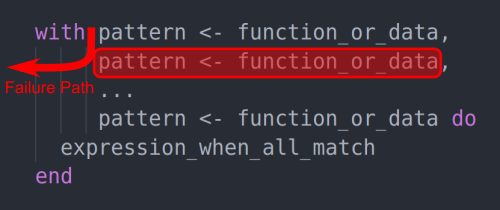

The first clause to not match stops the flow and the non-matching data is returned as the result.

When you see nested

casestatements in your code, you may want to use awithinstead.

Optional else

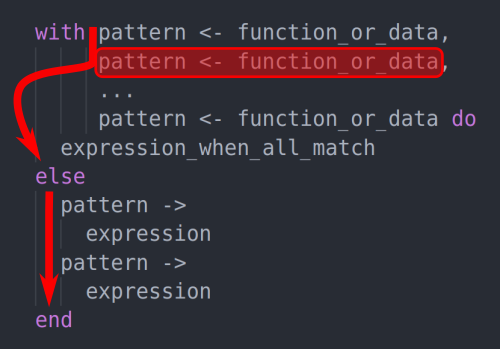

What if a step fails and we want to perform some special handling? To address this, the with statement supports an optional else clause. We only include it when we want to respond to an error. We may log the failure, transform the result or take some other action.

When we provide an else clause, instead of a match failure being returned right way, it skips any remaining steps and begins pattern matching the else clauses starting from the top. It stops at the first match and the expression is used as the return value.

The else clause pattern matches look more like a case. The arrows go to the right like a case statement. It behaves like a case as well so it should feel familiar.

Let’s re-visit the previous example. If a Map.fetch/2 call fails, it returns the atom :error.

data = %{width: 10}

with {:ok, width} <- Map.fetch(data, :width),

{:ok, height} <- Map.fetch(data, :height) do

{:ok, width * height}

end

#=> :errorPractice Exercise #1

Using your understanding of the else clause, match on the :error atom and instead return the error tuple and message {:error, "Invalid data"}.

Telling the Difference

This demonstrates a potential issue. How can you tell the difference between a missing :width or :height? In both cases it goes into the else as :error. Let’s consider a pseudo code example to illustrate the point. Assume we have two functions:

Users.one/1– returns a%User{}struct ornilif not foundCustomers.one/1– returns a%Customer{}struct ornilif not found

If I have a with statement like the one below, where I only consider it a match when I get the struct and not a nil result. Then the question is, if I end up in the else clause with a nil, how can tell if we didn’t find the user or if it was the customer that failed?

with %User{} = user <- Users.one(1),

%Customer{} = customer <- Customers.one(100) do

# return success result

else

nil ->

"???"

end

I can’t tell which failed! Patterns that did match and were bound are not available in the else clause to try and test for.

A common way to solve this is to not call functions that return a nil. Instead, call functions that return a result like {:ok, user} or {:error, "User not found"}. Then the cause of failure is clear. The more you adopt and use pattern matching in your applications, the more it impacts the design of your APIs. You want easier ways of matching and knowing if a call succeeds or not. Returning tuple results is a common way to do that.

But what if there are existing functions I need to call and they return something where I can’t tell the reason for a failure? There are a couple ways to deal with this issue.

- Create a local private function that calls the function you need and converts a

nilresult into an error with a message. - Wrap the function in a tuple in the

withstatement to identify where they come from.

Local Private Functions

Let’s re-visit the width and height example. Create local private functions to solve this issue:

defmodule Playing do

def compute_area(data) do

with {:ok, width} <- get_width(data),

{:ok, height} <- get_height(data) do

{:ok, width * height}

end

end

defp get_width(data) do

case Map.fetch(data, :width) do

{:ok, width} ->

{:ok, width}

:error ->

{:error, "Width not found"}

end

end

defp get_height(data) do

case Map.fetch(data, :height) do

{:ok, height} ->

{:ok, height}

:error ->

{:error, "Height not found"}

end

end

end

Playing.compute_area(%{width: 10})

#=> {:error, "Height not found"}

Playing.compute_area(%{height: 5})

#=> {:error, "Width not found"}Wrapping the Result

Another way to solve this is to wrap the function call in a tuple used to identify the result. The pattern match on the left side must unwrap it when successful. However, it is most helpful in the else when identifying why it failed.

defmodule Playing do

def compute_area(data) do

with {:width, {:ok, width}} <- {:width, Map.fetch(data, :width)},

{:height, {:ok, height}} <- {:height, Map.fetch(data, :height)} do

{:ok, width * height}

else

{:width, :error} ->

{:error, "Width not found"}

{:height, :error} ->

{:error, "Height not found"}

end

end

end

Playing.compute_area(%{width: 10})

#=> {:error, "Height not found"}

Playing.compute_area(%{height: 5})

#=> {:error, "Width not found"}Guard Clauses

Guard clauses are supported in both the patterns in the with clauses and the else clauses. Just be aware that this level of pattern matching is available to you.

data = %{width: 10, height: 5}

with {:ok, width} when is_number(width) <- Map.fetch(data, :width),

{:ok, height} when is_number(height) <- Map.fetch(data, :height) do

{:ok, width * height}

endExcessive Use

It is possible to over apply the with clause. I see people write a 1-line with clause and it feels excessive. Let’s see an example of two ways to write the same basic thing. One way uses with and the other uses case.

defmodule Example do

def excessive_with(data) do

with {:ok, width} <- Map.fetch(data, :width),

do: {:ok, width}

end

def using_case(data) do

case Map.fetch(data, :width) do

{:ok, width} ->

{:ok, width}

:error ->

{:error, "Width not found"}

end

end

endWhen learning a new language, it’s understandable that we “latch on” to a new idea that works. When you realize that a with can be used anywhere in place of a two pattern case statement, then it may be tempting to use the tool everywhere that it can work.

Personally, I value code with this mindset:

- Clarity > Brevity

- Explicit > Implicit

A one-line with statement is more brief and compact than the case version. However, the error return type doesn’t appear to have been given any thought. Exactly what it returns when it errors is unclear. In this case, Map.fetch/2 will return an :error atom when it fails. This now requires the caller of the excessive_with/1 function to know that they might get an :error back and have to deal with that. However, just a quick look into the the excessive_with/1 function won’t tell you what it returns on a failure. The reader has to read the code and know what Map.fetch/2 returns on a failure. The return value is implicit.

The case version is longer. It explicitly deals with the error response. It is more clear when glancing at the function what 2 return types it will have.

The with statement is powerful. It’s greatest power comes when chaining multiple patterns together. Avoid using a single-line with when a case works and can be clearer.

Strengths and Weaknesses

The with statement has it’s own set of strengths and weaknesses. Let’s consider what they are.

Strengths

- The

withstatement works well for pulling together different functions to create a Code Flow. The functions do not have to be created for the purpose. - Each step lets you pattern match and gather the values you need from one step to use in the next steps.

- Solves the nested

casestatement code-smell by making the “Happy Path” easier to see and reason about. - It is a light-weight pattern and can be used quickly to pull different operations together.

Weaknesses

- Any non-matching step in the sequence is returned immediately from a

withstatement. You need to think about the return types of all the functions you call. - If you provide an

elseclause, any match failure drops into theelsebody. Depending on the functions called in the steps, it may be difficult to identify which match failed. - When a match fails, you are left dealing with the non-match in a fairly disconnected way. In the Railway Pattern, you deal with the non-match in a purpose-built function.

When to use the With Statement?

Honestly, when dealing with a series of steps in your application, the with statement is likely your go-to solution. Most business logic is made of using lower level accessing functions to perform meaningful and deliberate operations.

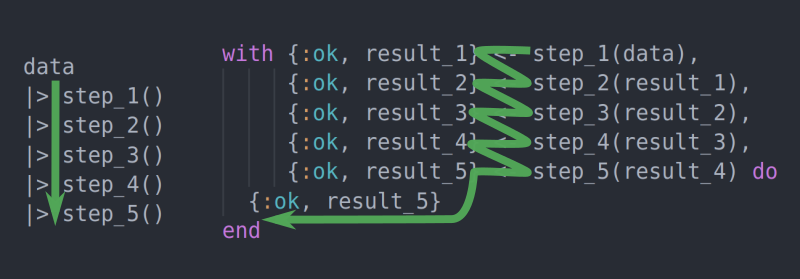

Compared to Railway

The with statement isn’t quite as clear and clean as the Railway Pattern’s top level “Happy Path” pipe. The “Happy Path” in the with clause is a little jagged by comparison. It doesn’t read quite as clearly.

However, the with statement does a better job of pulling together different functions in your project that weren’t designed to be part of the Railway Pattern. For this reason, and the brevity with which you can write with statements, you will likely find many applications and uses for this in your projects.

Handling errors is more explicit in the Railway Pattern because you already have functions dedicated to the step. If you have the need to deal with a step failure in more than a trivial way, then the Railway Pattern can work well. In the with statement, an error at any step is either returned as-is or drops into the else body where all other failures go as well. Depending on the error, it may not be easy to identify what went wrong in an else clause. For this reason, the with clause works best when pulling together functions that provide a good pattern matching result value.

Quick Note on Aliases

In Elixir, an alias can create a shortcut to a module in your code. Since the with statement makes it easier to pull together different parts of our application, this is a good time to start using aliases.

Let’s say the module we want to use is CodeFlow.Schemas.Order. Every time we call a function or reference the struct we’d be writing something like %CodeFlow.Schemas.Order{} which can be long, tedious, and error prone. Adding an alias in the file creates a shortcut to that module by just writing Order.

Be default, the shortcut name is the last segment of the namespace. The alias command also allows you to change the name. This is helpful if you encounter names that would otherwise collide.

# an alias can't be use on both as they'd both try and locally use `Order`

alias MyApp.Web.Controllers.Order

alias MyApp.Schemas.Order

# using `:as`, we can specify the name to use

alias MyApp.Web.Controllers.Order, as: OrderController

alias MyApp.Schemas.OrderRefer to the official documentation for more information. Note that we use a Keyword list to specify the :as option to alias.

You do not need to alias a module in order to use it. You can always use the fully qualified module name from anywhere in your application. An alias is most commonly used to give you a shortcut to the module so you can locally reference it in an abbreviated way.

Practice Exercise #2

In this exercise, you will complete the CodeFlow.With.place_new_order/3 function located in the download project in file lib/with.ex.

Write the with statement that performs the task of placing a new order for a customer. All of the supporting code is already prepared in the project. There are fake business layer contexts for working with Customers, Orders, and Items. There are structs that represent database entries as well.

Aliases are already created for you but commented out as they aren’t used yet.

Specification

- Find the customer –

Customers.find/1 - Find the item being ordered –

Items.find/1 - Start a new order –

Orders.new/1 - Add the found item to the order –

Orders.add_item/3 - Notify the customer of the new order –

Customers.notify/2 - Return

{:ok, order}when it succeeds

When notifying the Customer, you specify the “event” using a tuple like {:order_placed, order}.

The Customer.notify/2 function may fail with an {:error, :timeout}. There is a test case showing we want this translated into a friendlier error message.

Any other failures messages should be returned as an {:error, text_reason} tuple.

The tests to run are in test/with_test.exs. You choose the order you want to run them in.

mix test test/with_test.exsMake sure to checkout the solution once you are done! There are some more thoughts and points to consider.

Recap

Make sure you are comfortable using the with statement. It is a handy language feature and you are likely to encounter it frequently in Elixir projects.

- The

withstatement can be a good solution to a nestedcasecode-smell. - Any match failure in a

withclause is either returned immediately or drops into the optionalelseclause. - Pattern matching, including guard clauses, are used in the

withstatement and in thecase-likeelseclause as well. - The

withstatement complements the Railway Pattern. Thewithprovides a brief pipeline-like ability you can use anywhere. - Pulls disparate re-usable business logic functions together into an ad hoc flow.

Refer to the official docs on the with statement which provide additional examples and explanation.

4 Comments

Comments are closed on this static version of the site.

Comments are closed

This is a static version of the site. Comments are not available.